In the world of fluid dynamics, while centrifugal pumps handle the lion's share of water-like transfer duties, they hit a hard performance wall when faced with viscous, shear-sensitive, or precise metering applications. When the fluid becomes as thick as molasses, or when the process demands a guaranteed flow rate regardless of system pressure, the Positive Displacement Pump (PD Pump) is the engineering standard.

Unlike rotodynamic machines that rely on kinetic energy and velocity, a positive displacement pump operates on the principle of volume manipulation. It is a machine of precision and force, capable of handling fluids that would stall a standard impeller. For industries ranging from pharmaceutical dosing to heavy chemical polymer transfer, understanding the mechanics of these volumetric pumps is essential for system reliability.

This guide provides an in-depth technical analysis of PD pump mechanics, classification, and selection criteria, referencing the specific capabilities of Aulank’s industrial pump solutions, such as our Magnetic Drive Gear Pumps and high-viscosity fluid handling systems.

Defining the Volumetric Pump Working Principle

To answer "what is a positive displacement pump" technically, we must look at how it moves energy. A PD pump creates flow by trapping a fixed amount of fluid in a cavity and then forcing (displacing) that trapped volume into the discharge pipe.

The Cycle of Displacement:

- Suction (Expansion): As the pump element (gear, lobe, screw, or vane) moves, it expands the volume at the inlet side. This creates a partial vacuum, allowing atmospheric pressure to push liquid into the pump chamber.

- Encapsulation: The fluid is trapped within a cavity formed by the moving elements and the pump casing. Unlike a centrifugal pump, there is very little "slip" or backflow in a healthy PD pump.

- Discharge (Contraction): The pump elements continue to move, collapsing the cavity or forcing the fluid out of the chamber. Since liquids are incompressible, the fluid must go out the discharge port.

This mechanism results in a constant flow pump characteristic. The flow rate is directly proportional to the rotational speed (RPM) and is largely independent of the discharge pressure (until the motor's torque limit or the pump's burst pressure is reached). This differs fundamentally from centrifugal pumps, where flow decreases as pressure increases.

Classification of Displacement Pumps: Rotary vs. Reciprocating

While there are many displacement pump types, they generally fall into two kinetic categories: Reciprocating and Rotary. For the continuous industrial processes Aulank serves—such as chemical circulation and food processing—Rotary Positive Displacement Pumps are the primary focus.

Rotary Pumps

These pumps use rotating components to trap and move fluid. They provide a continuous flow with lower pulsation than reciprocating types.

- Gear Pumps: The workhorse of the hydraulic and chemical industries. Precision gears mesh to move fluid. Aulank utilizes Magnetic Drive Gear Pump technology to handle hazardous chemicals without leakage.

- Lobe Pumps: Similar to gear pumps but the rotating lobes do not touch. Ideal for sanitary applications and shear-sensitive fluids.

- Screw Pumps: Use one or more screws to push fluid axially. Perfect for high-flow, high-viscosity applications.

- Vane Pumps: Use sliding vanes that seal against the casing wall.

Reciprocating Pumps

These use a piston, plunger, or diaphragm to move fluid via an oscillating motion.

- Diaphragm Pumps: Often air-operated (AODD), used for slurries or acids.

- Piston Pumps: High-pressure washing or metering.

For most high-viscosity, steady-stream applications in the chemical process pump selection phase, Rotary pumps offer the best balance of efficiency, size, and reliability.

Centrifugal vs. Positive Displacement Pump: A Technical Comparison

Engineers often struggle with the centrifugal pump vs positive displacement decision. The choice is rarely about "better," but rather about "fitness for purpose."

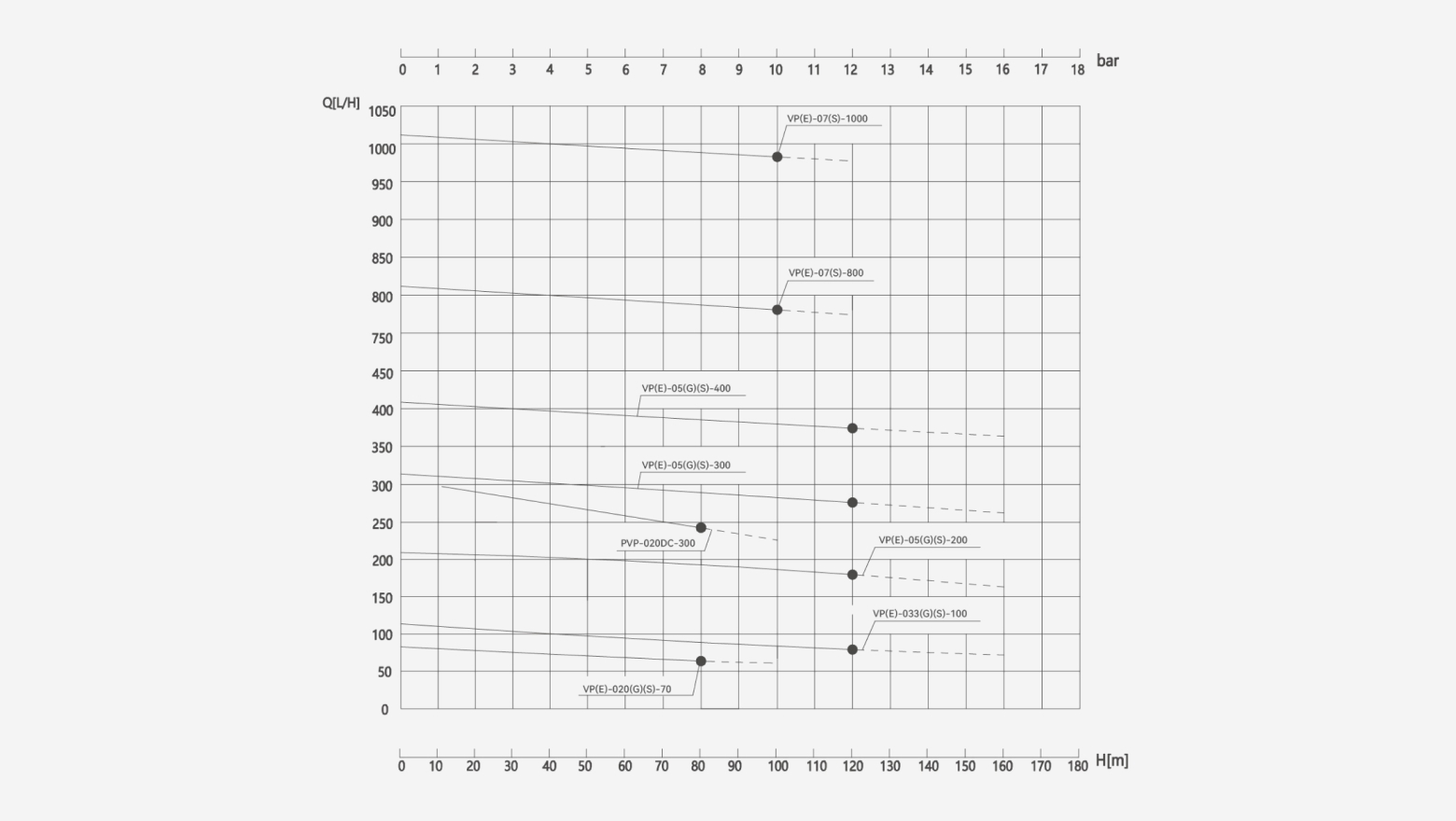

The most distinct difference lies in their performance curves. A centrifugal pump has a curved H-Q (Head-Capacity) relationship: as back-pressure rises, flow drops. A PD pump has a nearly vertical linear curve: flow remains constant even if pressure spikes.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics Comparison

| Feature | Centrifugal Pump | Positive Displacement (PD) Pump |

| Flow Mechanism | Kinetic Velocity (Impeller) | Volumetric Trap (Gear/Lobe/Screw) |

| Pressure vs. Flow | Flow drops as pressure rises | Flow is constant regardless of pressure |

| Viscosity Limit | Efficient < 200 cPs | Efficient > 200 cPs (up to 1,000,000 cPs) |

| Efficiency Trend | Decreases as viscosity rises | Increases as viscosity rises (less slip) |

| Self-Priming | No (requires foot valve/priming) | Yes (creates strong vacuum) |

| Shear Sensitivity | High Shear (damages delicate fluids) | Low Shear (Lobe/Screw types) |

| Run Dry Capability | Limited (seal damage) | Very Poor (galling risk) |

This comparison highlights why Aulank recommends industrial centrifugal pumps for water and solvents, but switches to positive displacement solutions for resins, polymers, and heavy oils.

Handling Viscous Fluids: Why PD Pumps Excel

The defining capability of a viscous fluid pump is its response to fluid thickness. When a centrifugal pump tries to move thick liquid (like heavy crude oil or syrup), energy is wasted due to friction on the impeller disk (disk friction), causing efficiency to plummet.

In contrast, a PD pump's efficiency actually improves with viscosity.

- Internal Slip Reduction: In any rotary pump, there is a tiny clearance between the rotating element and the casing. With thin fluids (like water), some fluid slips back from the high-pressure discharge to the suction side.

- Viscous Sealing: When pumping thick fluids, the fluid itself acts as a sealant in these clearances, reducing pump slippage to nearly zero. This results in high volumetric efficiency.

For industries handling products like adhesives, chocolate, bitumen, or polyols, the high viscosity pump is not an option; it is a necessity. Aulank’s solutions for these applications often involve jacketed casings to maintain fluid temperature and prevent the medium from solidifying inside the pump during pauses.

Gear Pump Mechanics: Internal vs. External Designs

Among rotary PD pumps, the gear pump working principle is the most common in chemical and lubrication sectors.

External Gear Pumps

Two interlocking gears (a driver and an idler) rotate in opposite directions. Fluid is trapped in the pockets between the gear teeth and the casing wall, traveling around the outside of the gears.

- Pros: High pressure, compact, inexpensive.

- Cons: Cannot handle solids; high shear.

- Aulank Application: Used in our Magnetic Drive Gear Pump series for dosing corrosive chemicals where leakage is unacceptable.

Internal Gear Pumps

A larger rotor gear drives a smaller idler gear located inside it. A crescent-shaped partition separates the suction and discharge zones.

- Pros: Better for high-viscosity fluids, lower shear, robust.

- Cons: Larger footprint than external types.

When selecting a rotary gear pump, material hardness is critical. For abrasive viscous fluids, hardened steel or coated gears are required to prevent rapid wear of the tolerances.

Flow Control and Metering Capabilities

One of the significant positive displacement pump advantages is the linear relationship between speed and flow.

Because the volume per revolution is fixed, PD pumps serve as excellent metering pumps. By utilizing a Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) or a gearbox, operators can control the dosing rate with extreme precision (often within ±0.5% accuracy).

This makes them ideal for:

- Chemical Dosing: Injecting precise amounts of catalyst or additive into a reactor.

- Filling Lines: Dispensing exact volumes of shampoo, oil, or sauce into containers.

- Proportional Blending: Mixing two viscous streams at a fixed ratio.

Unlike centrifugal pumps, where flow control often requires throttling valves (which wastes energy), flow control in PD pumps is achieved by simply changing the motor speed, making them an energy efficient industrial pump choice for variable process demands.

Aulank’s Approach: Leak-Free Magnetic Drive Gear Pumps

Standard gear pumps suffer from shaft seal leaks, especially when handling thin, penetrating solvents or toxic chemicals. Aulank addresses this by combining positive displacement technology with our core competence: Sealless Magnetic Drives.

The Aulank Solution

By removing the dynamic shaft seal and replacing it with a static containment shell, our hermetic gear pumps offer the high-pressure, metering benefits of a gear pump with the safety of a leak-proof mag-drive.

- Applications: Pumping isocyanates, acids, and hazardous solvents.

- Material: Available in Stainless Steel 316L or specialty alloys for maximum chemical resistance.

- Protection: Integrated with dry-run protection logic to prevent the gears from seizing if the supply tank runs empty.

This hybrid approach ensures that clients in the New Energy (Battery Electrolyte) and Chemical sectors do not have to choose between "precise flow" and "leak-free safety"—they get both.

Troubleshooting and Maintenance of PD Pumps

While robust, troubleshooting PD pumps requires a different mindset than centrifugal pumps. The most critical rule is:

Never run a PD pump against a closed discharge valve.

The Pressure Trap

Because the pump pushes a fixed volume, if the discharge is blocked, pressure will rise instantly until something breaks (the pipe, the pump casing, or the motor shaft).

- Safety Requirement: A Pressure Relief Valve (PRV) must always be installed on the discharge line or integrated into the pump cover.

Common Failure Modes

- Noise/Cavitation: Even PD pumps can cavitate if the fluid is too viscous for the inlet port size or speed. This is often called "starvation." Solution: Slow down the pump or increase the suction line diameter.

- Slip/Flow Loss: If flow drops while speed is constant, it usually indicates wear on the gear teeth or casing, widening the internal clearances.

- Dry Running: The tight tolerances of rotary pumps rely on the fluid for lubrication. Dry running leads to "galling" (metal-on-metal welding) and catastrophic seizure.

Conclusion

The Positive Displacement pump is the precision instrument of the fluid handling world. Whether moving shear-sensitive food products with a lobe pump, metering chemical additives with a gear pump, or transferring heavy sludge with a screw pump, these machines offer capabilities that centrifugal pumps simply cannot match.

For industrial systems dealing with high viscosity, high pressure, or precise dosing, the PD pump is the correct engineering choice. At Aulank, we enhance this technology by integrating it with leak-free magnetic drive systems, providing solutions that are not only efficient but also compliant with the strictest safety and environmental standards.